OPINION

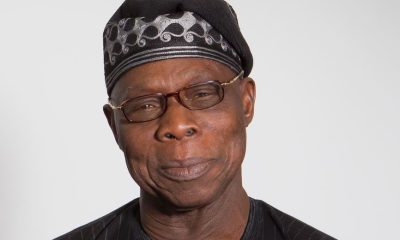

How Obasanjo Ruined Peter Obi’s Chances

By Rudolf Okonkwo

This is the story of how Olusegun Obasanjo’s support of the structure of criminality ruined Peter Obi’s chances, transformed Anambra State and produced the Peter Obi currently on the national stage. It is also a story of how Obasanjo is trying to make amends in the late hours of his life, hoping to make heaven.

During the 2004 World Igbo Congress Convention in New Jersey, Chekwas Okorie, the then chairman of All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA), told a few of us inside a hotel room what happened between him and Olusegun Obasanjo during the 2003 elections in Nigeria. Chekwas Okorie’s story illustrated who Bola Tinubu, then governor of Lagos State, was and how he differed from Peter Obi.

According to Chekwas Okorie, in 2003, APGA won the election in four of the five South-Eastern states. But the PDP rigging machine, now known as structure, rigged APGA’s governorship candidates out. In those days of an unholy alliance between President Olusegun Obasanjo and INEC’s Chairman, Maurice Iwu, they wasted no time with sophisticated rigging methods. They simply wrote the desired results and handed them to INEC officials to announce.

When INEC announced the result of the 2003 elections, Chekwas Okorie went to Olusegun Obasanjo to complain. Obasanjo acknowledged the rigging and promised to hand two or three states back to APGA. He asked Chekwas Okorie to go and consult his party on which states he would like Obasanjo to hand over to APGA.

During the same election, PDP had plans to rig the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN) out of the South West. As the results were being published online on the INEC website, all the South-Western states were falling to PDP. When the then Lagos State governor, Bola Tinubu, saw what was happening, he called President Obasanjo. He told Obasanjo that he had in his command 10,000 area boys with gallons of petrol ready to burn down federal government properties in Lagos if INEC announced that he lost to PDP.

In the words of Chekwas Okorie, Obasanjo immediately called Maurice Iwu and asked him to leave Lagos State alone. That was how Lagos State was left alone, while other states in the South-West became PDP states.

Meanwhile, Chekwas Okorie returned to Obasanjo days after the election. He had consulted his party people and they had chosen the three states he wanted Obasanjo to hand over to APGA. One of the states was Anambra.

At this point, Obasanjo had seen that all was calm in the South-East. The people had accepted their fate and moved on. Obasanjo told Chekwas Okorie off and asked him to go and do his worse.

This act of condoning the structure of criminality on the part of Olusegun Obasanjo gave Anambra State the governorship of Dr Chris Ngige.

Another bombshell dropped a day after Chekwas Okorie told us the story above. In the same conference, Obasanjo’s boy, Chris Ubah, acknowledged in front of Governor Chris Ngige and Anambra State indigenes that he was the person who wrote the results of the Anambra State gubernatorial election and handed over the paper to an INEC officer who read it out to the world. He pointed at Peter Obi, who was in the audience, and said, this was the man who won the election.

Peter Obi did not give up on his stolen mandate, unlike the APGA gubernatorial candidates in other Southeastern States. He fought in several courts for almost three years. It culminated in the court kicking out Dr Ngige as governor in March 2006. It did not end there. Enforcers of Obasanjo’s structure of criminality did not leave Peter Obi to govern the state in one piece. The hoodlums who burnt down government offices and radio stations under Governor Chris Ngige in November 2004 continued to attack. In October 2006, they burnt down the governor’s lodge in Onitsha. It was part of well-orchestrated efforts by the same hoodlums enjoying the cover of then President Olusegun Obasanjo to unleash mayhem on the state. Their suit-and-tie colleagues in the State House of Assembly impeached the governor twice. Peter Obi survived all those attempts and became stronger in the end.

So, days after the 2023 presidential election, when Obasanjo walked out to make a press statement denouncing the conduct of the exercise, those of us from Anambra State had a different take on the words coming out of his mouth. To us, Obasanjo sounded like a man who had forgotten these incidents of the past. But the truth is that he did not.

In a leaked audio that Charly Boy initially denied but later confirmed, Obasanjo had wanted the musician to lead a protest in Lagos and Abuja against INEC’s declaration of Bola Tinubu as the president-elect. In Charly Boy’s version of events, Obasanjo later called him back and asked him not to proceed with the protest for fear that the Nigerian military would kill protesters.

We can forgive those young people who think Obasanjo became penis-shy about protest because of the EndSARS killings. No. During Obasanjo’s eight years as president, he supervised the Nigerian military’s massacre of unarmed civilians.

Under Obasanjo’s order, on 20 November, 1999, the Nigerian military invaded Odi in Bayelsa State and killed over 900 people. The military’s excuse was that a gang of Niger Delta militants killed twelve police officers days before. In a February 2013 judgment, the Federal High Court ordered the Federal Government to pay N37.6 billion compensation to the people of Odi for the Nigerian military’s massacre and burning down of their town. In May 2014, Jonathan’s administration paid N15 billion as compensation.

Again under Obasanjo’s order, the military attacked Zaki-Biam in Benue State in October of 2001 and killed over 200 people. The military gave the excuse that they went to enforce order in a region of Tiv villages where militants killed 19 soldiers. Amongst those killed were women, children, and the elderly. The Nigerian government initially denied the killings. President Umaru Yar’Adua later apologised in 2007 during a visit to Benue.

Like most African politicians, Olusegun Obasanjo has used the first part of his life to destroy the last. Like his fellow co-travelers on the disgusting path, Obasanjo’s last-minute effort to crossover to the decent road almost always hits a roadblock, a remnant of the structure of criminality with which he used to be in bed. He can pretend to show pertinence for his sins, but as his powers wean, he can only pray – for Buhari to do something, for the people to rise, for the international community to intervene, for the God in heaven to strike. But as we have repeatedly seen, regret comes at the end.

Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo teaches Post-Colonial African History at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He is also the host of “Dr. Damages Show.” His books include This American Life Sef, Children of a Retired God, among others

Education

Varsity Don Advocates Establishment of National Bureau for Ethnic Relations, Inter-Group Unity

By David Torough, Abuja

A university scholar, Prof. Uji Wilfred of the Department of History and International Studies, Federal University of Lafia, has called on the Federal Government to establish a National Bureau for Ethnic Relations to strengthen inter-group unity and address the deep-seated ethnic tensions in Nigeria, particularly in the North Central region.

Prof.

Wilfred, in a paper drawing from years of research, argued that the six states of the North Central—Kwara, Niger, Kogi, Benue, Plateau, and Nasarawa share long-standing historical, cultural, and economic ties that have been eroded by arbitrary state boundaries and ethnic politics.According to him, pre-colonial North Central Nigeria was home to a rich mix of ethnic groups—including Nupe, Gwari, Gbagi, Eggon, Igala, Idoma, Jukun, Alago, Tiv, Birom, Tarok, Angas, among others, who coexisted through indigenous peace mechanisms.

These communities, he noted, were amalgamated by British colonial authorities under the Northern Region, first headquartered in Lokoja before being moved to Kaduna.

He stressed that state creation, which was intended to promote minority inclusion, has in some cases fueled exclusionary politics and ethnic tensions. “It is historically misleading,” Wilfred stated, “to regard certain ethnic nationalities as mere tenant settlers in states where they have deep indigenous roots.”

The don warned that such narratives have been exploited by political elites for land grabbing, ethnic cleansing, and violent conflicts, undermining security in the sub-region.

He likened Nigeria’s ethnic question to America’s historic “race question” and urged the adoption of structures similar to the Freedmen’s Bureau, which addressed racial inequality in post-emancipation America through affirmative action and equitable representation.

Wilfred acknowledged the recent creation of the North Central Development Commission by President Bola Tinubu as a step in the right direction, but said its mandate may not be sufficient to address ethnic relations.

He urged the federal government to either expand the commission’s role or create a dedicated Bureau for Ethnic Relations in all six geo-political zones to foster reconciliation, equality, and sustainable development.

Quoting African-American scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, Prof. Wilfred concluded that the challenge of Nigeria in the 21st century is fundamentally one of ethnic relations, which must be addressed with deliberate policies for unity and integration.

OPINION

The Pre-2027 Party gold Rush

By Dakuku Peterside

The 2027 general elections are fast approaching, and Nigeria’s political landscape is undergoing a rapid transformation. New acronyms, and freshly minted party logos are emerging, promising a new era of renewal and liberation.To the casual observer, this may seem like democracy in full bloom — citizens exercising their right to association, political diversity flourishing, and the marketplace of ideas expanding.

However, beneath this surface, a more urgent reality is unfolding. The current rush to establish new parties is less about ideological conviction or grassroots movements and more about strategic positioning, bargaining leverage, and transactional gain.It is the paradox of Nigerian politics: proliferation as a sign of vitality, and as a symptom of democratic fragility. With 2027 on the horizon, the political air is electric, not with fresh ideas, but with a gold rush to create new political parties.Supporters call it the flowering of democracy. But scratch the surface and you will see something else: opportunism dressed as pluralism. This is not just politics; it is political merchandising. Parties are being set up like small businesses, complete with negotiation value, resale potential, and short-term profit models. Today, Nigeria has 19 registered political parties, one of the highest numbers in the world behind India (2,500), Brazil (35), and Indonesia (18).History serves as a cautionary tale in this context. Whenever Nigeria has embraced multi-party politics, the electoral battlefield has eventually narrowed to a contest between two main poles. In the early 1990s, General Ibrahim Babangida’s political transition programme deliberately engineered a two-party structure by decreeing the creation of the National Republican Convention (NRC) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP).His justification was rooted in the observation — controversial but not entirely unfounded — that Nigeria’s political psychology tends to gravitate toward two dominant camps, thereby simplifying voter choice and fostering more stable governance. Pro-democracy activists condemned the move as state-engineered politics, but over time, the pattern became embedded.When Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1999, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) emerged as the dominant force, facing off against the All People’s Party (APP) and Alliance for Democracy (AD) coalition. The 2003 and 2007 elections pitted the PDP against the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP); in 2011, the PDP contended with both the ANPP and the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC).By 2015, the formation of the All Progressives Congress (APC) — a coalition of the CPC, ANPP, Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), and a faction of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) — restored the two-bloc dynamic. This ‘two-bloc dynamic’ refers to the situation where most of the political power is concentrated within two main parties, leading to a less diverse and competitive political landscape. Even when dozens of smaller parties appeared on the ballot, the real contest was still a battle of two heavyweights.And yet, here we are again, with Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) registering nineteen parties but facing an avalanche of new applications — 110 by late June, swelling to at least 122 by early July. This surge is striking, especially considering that after the 2019 general elections, INEC deregistered seventy-four parties for failing to meet constitutional performance requirements — a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in 2021.That landmark ruling underscored that party registration is not a perpetual license; it is a privilege conditioned on meeting electoral benchmarks, such as a minimum vote share and representation across the federation. The surge in party formation could potentially lead to a more complex and fragmented electoral process, making it harder for voters to make informed decisions and for smaller parties to gain traction.So, what explains the surge in the formation of new parties now? The reasons are not mysterious. Money is the bluntest answer, but it is woven with other motives. For some, creating a party is a strategic move to position themselves for negotiations with larger parties — trading endorsements, securing “alliances,” and even extracting concessions like campaign funding or political appointments.Others set up “friendly” parties designed to dilute opposition votes in targeted constituencies, often indirectly benefiting the ruling party. Some political entrepreneurs build parties as personal vehicles for regional ambitions or as escape routes from established parties, where rival factions have captured the leadership.Some are escape pods for politicians frozen out of the ruling APC’s machinery. There is also a genuine democratic impulse among certain groups to create platforms for neglected ideas or underrepresented constituencies. But the transactional motive often eclipses these idealistic efforts, leaving most new parties as temporary instruments, rather than enduring institutions.The democratic consequences of this kind of proliferation are profound. On one hand, political pluralism is a constitutional right and an essential feature of democracy. On the other hand, too many weak, poorly organised parties can fragment the opposition, confuse voters, and degrade the quality of political competition.Many of these micro-parties lack ward-level presence, a consistent membership drive, and ideological coherence. Their manifestos are often generic, interchangeable documents crafted to meet registration requirements, rather than to present a distinct policy vision. On election-day, their presence on the ballot can be more of a distraction than a contribution, and after the polls close, many vanish from public life until the next cycle of political registration. This is not democracy — it is ballot clutter.This is not uniquely Nigerian. In India, a few thousands registered parties exist, yet only a fraction of them is active or competitive at the state or national level. Brazil, notorious for its highly fragmented legislature, has struggled with unstable coalitions and governance deadlock; even now, it is reducing the number of effective parties.Indonesia allows many parties to register but imposes a parliamentary threshold — currently four per cent of the national vote — to limit legislative fragmentation. These examples, along with others from around the world, suggest that plurality can work, but only when paired with guardrails: stringent conditions for registration, clear criteria for participation, performance-based retention, and an electoral culture that rewards sustained engagement over fleeting visibility.Nigeria already has a version of this in place, courtesy of INEC’s power to deregister. We deregistered seventy-four parties in 2020 for failing to meet performance standards, and five years later, we are sprinting back to the same cliff.Yet, loopholes remain especially, and the process is reactive rather than proactive. Registration conditionalities are lax. This is where both INEC and the ruling APC must shoulder greater responsibility. The need for electoral reform is urgent, and it is time for all stakeholders to act.For INEC, the task is to strengthen its oversight by tightening membership verification, enhancing financial transparency, and expanding its geographic spread requirements, as well as introducing periodic revalidation between election cycles.For the ruling party, the challenge lies in upholding political ethics: resisting the temptation to exploit party proliferation to splinter the opposition for short-term gain. A strong ruling party in a democracy wins competitive elections, not one that manipulates the field to run unopposed. Strong democracy requires a credible opposition, not a scattering of paper platforms that cannot even win a ward councillor seat.Here is the truth: this system needs reform. Reform doesn’t mean closing the democratic space, but making it meaningful and orderly. Democracy must balance full freedom of association with the need for order. While freedom encourages many parties, order requires limiting their number to a manageable level.For example, Nigeria could require parties to have active structures in two-thirds of states, a verifiable membership, and annual audited financials. Parties failing to win National Assembly seats in two consecutive elections could lose registration.The message to new parties is clear: prove you’re more than just a logo and acronym. Build lasting movements — organise locally, offer real policies alternatives, and stay engaged between elections.Democracy is a contest of ideas, discipline, and trust. If the 2027 rush is allowed to run unchecked, we will end up with the worst of both worlds — a crowded ballot and an empty choice. Mergers should be incentivised through streamlined legal processes and possibly electoral benefits, such as ballot priority or increased public funding. At the same time, independent candidates should be allowed more room to compete, ensuring that reform does not entrench an exclusive two-party cartel.Ultimately, the deeper issue here is the erosion of public trust. Nigerians have no inherent hostility to new political formations; what they distrust are political outfits that emerge in the months leading up to an election, strike opaque deals, and disappear without a trace. Politicians must resist the temptation to treat politics as a seasonal business opportunity and instead invest in it as a long-term public service.As 2027 approaches, Nigeria stands at a familiar but critical juncture. The country can indulge the frenzy — rolling out yet another logo, staging yet another press conference, promising yet another “structure” that exists mainly on paper. Or it can seize this moment to rethink how political competition is structured: open but disciplined, plural but purposeful, competitive but coherent.Fewer parties will not automatically make Nigeria’s democracy healthier. But better parties — rooted in communities, committed to clear policies, and resilient beyond election season — just might. And that is a choice within reach, if those who hold the levers of power are willing to leave the system stronger than they found it.Dakuku Peterside, a public sector turnaround expert, public policy analyst and leadership coach, is the author of the forthcoming book, “Leading in a Storm”, a book on crisis leadership.OPINION

Call for National Youth Career Development Initiative

By Blessing Adeoti

Nigerian youths are intelligent and hardworking, but very few have a solid career development plan. It doesn’t matter whether a student graduates with first-class honours or shows great potential; most focus on just one goal: earning a degree or certificate from a higher institution and then seeking job opportunities.

The main issues are the lack of available jobs, and nowhere in the world is it necessary for the government to guarantee employment for everyone. Moreover, not every student who attends a higher institution needs to follow such a path.Most people may be better suited to alternative routes, such as technical or vocational training, to develop competent professionals in industries that lack sufficient specialised expertise, including electricians, carpentry, plumbing, welding, mechanics, computer skills, and others. These are skills in high demand that will enable the youth to contribute meaningfully to the economy, even as entrepreneurs.Although President Bola Tinubu’s administration is trying to revive the technical colleges, what orientation do the students have to embrace the unique opportunities? Should we blame the youths for lacking this foresight? No! The root of the problem lies in the absence of structured career counselling in Nigeria’s educational system.Nigerian youths face the challenges of navigating the uncertainty in career pursuits. This is not because they lacked aspirations, but rather due to the near-total absence of a functional career counselling system within the Nigerian education sector. Nigeria’s career counselling vacuum dates to the colonial education system, which was mainly designed to produce clerks, administrators, and workers for the service sector. The focus was never on helping students discover their strengths or guiding them toward career paths that could help them achieve their full potential.After independence, the National Policy on Education of 1977, revised in 2013, mandated the introduction of guidance and counselling services in schools, but implementation has been significantly inadequate. Globally, the economic and job realities have changed. As a university lecturer, I have seen firsthand the struggles many students face, yet not one has ever had experience with a career guide or counsellor.In 2020, the Institute of Counselling in Nigeria revealed that only 15 per cent of secondary schools have functional counselling units, and many of these are staffed by untrained personnel. This neglect has produced a generation of aimless graduates, unemployment, underemployment, and skills mismatches. It signals a disconnect between the education system and the labour market, as graduates are often unprepared for the skills required in today’s economy.Economically, the World Bank estimates that youth unemployment costs Nigeria billions in lost GDP annually. The psychological effects are equally devastating. Career indecision is linked to anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression among young Nigerians, according to a 2021 study from the University of Ibadan, which found that many students trapped in unsuitable career paths experienced significant psychological distress.Socially, this has contributed to increased crime, cultism, extremism and terrorism across the country. Nigeria’s crime rate, ranked 7.28 out of 10 globally, is partly fuelled by jobless youth seeking alternative livelihoods.There is hope for change as President Bola Tinubu’s administration has shown a genuine commitment to supporting Nigerian youth. The President’s Renewed Hope agenda for education, including the Nigeria Education Loan Fund and the revitalisation of Nigeria’s technical and vocational colleges, is commendable.However, these efforts risk falling short without the addition of a well-structured national youth career development programme. There are proven models from around the world that Nigeria can adapt to address this challenge. For example, Finland, renowned for its world-class education system, places a strong emphasis on career guidance.From an early age, Finnish students receive career counselling as part of their school curriculum. Trained career counsellors work closely with students to identify their strengths, interests, and goals. Similarly, Singapore implemented the education and career guidance programme, which aligns student aspirations with workforce needs, helping the country maintain youth unemployment below 5 per cent (Singapore Ministry of Education, 2024).In Australia, the National Career Education Strategy prepares young people for the future of work by integrating career education into the school curriculum, emphasising transferable skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability.President Tinubu’s administration can rebuild Nigeria’s system by launching an aggressive youth career development initiative that ensures the President’s educational reforms translate into tangible outcomes.Such an initiative would equip students with the clarity and direction needed to fulfil both their personal aspirations and national economic needs. This is about giving young Nigerians the tools, confidence, and clarity to chart their career developmental paths.With renewed focus and investment, the government now has a real chance to correct past mistakes and help young Nigerians build brighter, more diverse career futures. There are many ideas for structures that could produce excellent results within a year, but Nigeria needs someone, or a team of passionate individuals, to turn them into reality.I recommend that President Tinubu appoint a special adviser for the National Youth Career Development Initiative to avoid the unnecessary bureaucracy that slows down many good initiatives. The special adviser must be an innovative thinker, a visionary leader with empathy and a deep understanding of Nigeria’s youth and job market dynamics, and a passion for empowering the next generation.The candidate would advise the President on a viable initiative for a national youth career development programme and work with other stakeholders. The government must take the lead by prioritising career counselling in its education policies and enforcing the establishment of functional guidance units in all schools.Dr Adeoti writes from Hong Kong via badeoti3@gmail.com