OPINION

The Impact of Incessant Attacks in Farming Communities

By Efe Omoghene

Rural communities across Nigeria’s Middle Belt and the North, which were once the major cities’ food pipeline, are now struggling to feed themselves. Thriving farmlands now bear the weight of fear and insecurity. With each disrupted planting season, the country edges closer to a more profound food security crisis, exacerbating what began as a regional instability into a nationwide emergency.

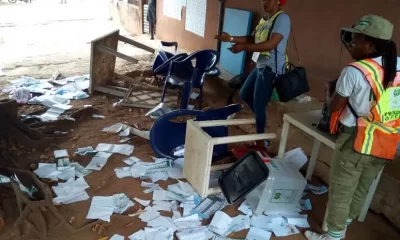

Incessant attacks have led to deaths and the displacement of farming communities in states that contribute significantly to Nigeria’s agricultural output. In June alone, attacks in Benue State, the “Food Basket of the Nation”, claimed dozens of lives and uprooted entire communities. While these incidents are heartbreaking, they are not new; we are only witnessing frequent recurrence. This troubling pattern of insecurity continues to force farmers off their land, disrupt food production, and weaken the nation’s ability to feed itself.Statistics from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre show that an estimated 295,000 internal displacements related to conflicts and violence were reported in Nigeria in 2024 alone. This includes the states of Benue, Borno, Katsina, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara. This is not just a crisis of safety; it’s a crisis of sustenance.For years, states such as Benue, Kaduna, Niger, Plateau, and Zamfara have been key food-producing regions, responsible for much of Nigeria’s grains, roots, fruits, and livestock. However, these areas are increasingly becoming places where violence has made farming a risky endeavour. Clashes between herders and farmers, banditry, terrorism, and communal violence have transformed fertile lands into contested zones. When farmers fear for their safety, they often cease farming or abandon their land altogether.The impact is already being felt. Markets are seeing rising prices on staple foods like yams, rice, and tomatoes. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the cost of beans in the country in October 2024 was 282 per cent higher compared to the same period in 2023.The Food and Agriculture Organisation’s trend analysis for the north-eastern states indicates persistently high or increasing levels of food insecurity since 2018. The number of people needing urgent aid has increased by at least four million annually during the lean seasons since June 2020. Additionally, the north-west and parts of the north-central regions now exhibit critical levels of severe food insecurity and malnutrition, identifying them as major hunger hotspots requiring urgent attention from policymakers.A study revealed that 52.44 per cent of respondents in Niger State experienced food insecurity due to various insecurity activities such as blocking local routes, killings, kidnapping, and disruption of market functions. Insurgencies in the North Central states have also contributed to rising poverty levels among livestock farming households, with 83.84 per cent of livestock farmers participating in a study reporting significant declines in livestock production due to insurgency.If this pattern continues unchecked, the consequences could be long-term. More families will face hunger, and young people will leave rural areas for safety and work, draining the agricultural workforce in rural communities. Dependence on humanitarian aid will rise, and the burden on government resources will increase.This year, Nigeria is already projected to face a significant hunger gap, with up to 33 million people at risk of acute food insecurity in the lean season (between June and August), according to the FAO. This represents a seven million-person increase from the same period in 2023.Food security is not solely the government’s responsibility. It is a basic human right and our collective responsibility. Relying solely on farmers in distressed areas is not a very practical approach. Thankfully, the country is not in a hopeless situation.Across Nigeria, there are numerous examples of humanitarian and community-led peacebuilding efforts in action, and Sahel Consulting is proud to be part of this momentum. We are actively collaborating with local and international partners to develop practical solutions in the food value chain, empowering farmers and strengthening agribusinesses across Nigeria.Through our programs in dairy, seed, tuber, and policy systems, we are facilitating the increase in productivity, improving market access, and building capacity at the grassroots level. Whether it’s training dairy farmers in Adamawa, scaling clean seed yam innovations in Benue, advancing true potato seed systems in Plateau, or improving livestock nutrition through feed and fodder initiatives, our work is rooted in collaboration, innovation, and long-term impact.Similar efforts are taking shape through the work of the Gates Foundation. Gates Ag One, in partnership with the Institute for Agricultural Research at the Ahmadu Bello University, Kaduna State, is providing farmers with access to improved seed varieties for crops like beans and maize, engineered to resist pests and withstand drought. The foundation also funds projects to enhance livestock productivity and strengthen dairy value chains.State governments have also started implementing policies to support ranching to address farmer-herder conflicts and enhance agricultural productivity. Eleven states, including Anambra, Bauchi, Delta, Jigawa, Kano, Lagos, Niger, Nasarawa, Ondo, Plateau, and Zamfara, are either allocating land for ranches, developing policies, or committing to do so in the future. This initiative is part of a broader shift from open grazing to more modern, sustainable ranching practices. Farmer-herder dialogues, early warning systems, and conflict mediation groups have all demonstrated promise.Private organisations are also collaborating with ministries, agencies, and local partners to support resilient food systems through training, innovation, and market access.This is by no means the end of the story. While these efforts are commendable, their impact is not particularly noticeable vis-à-vis the insecurity, as they are implemented in isolation and on a relatively small scale. The real challenge, and opportunity, lies in collaboratively scaling initiatives that are working. For lasting change, we need to invest more in proven interventions. Government policies must be supported by robust implementation strategies, and private and development actors must be empowered to apply these models in more communities across the country.It is not enough to initiate these projects; we must establish frameworks that ensure they are sustainable, community-led, and responsive to the realities of the local communities. Clear safeguards and inclusive principles must be in place, especially in areas where displacement and land rights are already sensitive issues. Any solution must consider the voices of host communities and guarantee mutual benefit.Let’s focus on what’s already showing promise, such as improved seed distribution, inclusive value chain optimisations, and community-based peacebuilding. But let’s also be honest: we need to do much more, and we must do it together.The key is to make human security a foundation, not an afterthought, for agricultural development. Farmers need more than seeds and tools. They need to know that if they invest in their land, neither their lives nor their farms will be lost to violence; if they plant, they will live to harvest.Food security starts with human security. When fields are safe, they flourish. And when rural communities thrive, the whole country benefits—from Lagos to Maiduguri, Port Harcourt to Makurdi.Efe Omoghene is the strategic communications officer with Sahel ConsultingOPINION

President Bola Tinubu: Establish a National Bureau for Ethnic Relations and Inter Group Unity

By Wilfred Uji

I once wrote an article based on a thorough research that all the states of North Central of Nigeria, Kwara, Niger, Kogi, Benue, Plateau and Nasarawa States, share a great deal of historical relations, resources, ethnicity and intergroup relations. These states have a common shared boarders with common security challenges that can only be effectively managed and resolved from a regional perspective and framework.

The exercise at the creation of states have overtime drawn arbitrary boundaries which in contemporary times are critical security and developmental issues that affects the sub region.

Firstly is the knowledge and teaching of history that can help grow and promote a regional unity and intergroup relations.

As far back as the pre-colonial era, the North Central of Nigeria had a plethora of multi ethnic groups which co-existed within the framework of mutual dependence exploiting indigenous peace initiatives. The diverse ethnic groups comprising of Nupe, Gwari, Gbagi, Eggon, Igala, Idoma, Jukun, Alago, Tiv, Gwanadara, Birom, Tarok, Angas, etc were independent state sovereignties before the advent of British colonial rule by the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Secoundly that British colonialism for economic and political exigencies almagamated all these ethnic groups under the Northern Region with headquarters first at Lokoja and later moved to Kaduna.

The indirect rule policy placed all the traditional political chiefdoms of the sub region under the political supervision, for the convience of taxation and draft labor, under the Sokoto Caliphate.

The indirect rule political structure was not intended to be a game changer that would enforce the dominance and hegemony of the Sokoto Caliphate over the people, land and resources of the sub region.

Thirdly, in the realization of the above, the British colonial state first created the Munchi Province and later the Benue Province as a political and state framework that could accommodate all the ethnic diversity of some of the North Central people.

State creation which ought to allow room for minority representation and expression, over time, has been turned upside down, by some ethnic groups as a vehicle of the exclusion of some minority groups.

For instance, the creation of Benue State in 1976 and Nasarawa State in 1996, does not signify and imply the exclusion of the Tiv and Idoma from Nasarawa State as well as the exclusion of the Alago and Jukun from Benue State.

These ethnic groups, long before state creation, had indigenous roots in all the states of the North Central of Nigeria. Historically, it is misleading and erroneous for these ethnic nationalities to be regarded as tenant settlers in the states where they are located.

The term tenant settlers have been used by the ruling political class of some states of the North Central of Nigeria as a staging point for land grabbing, genocide, land claims and struggles that has created a night mare for the security landscape of the region. In contemporary times, there is no denying the fact that there is an ethnic question in the North Central of Nigeria where there has been a revival of ethnic nationalism by some irredentist groups reinforced by revisionist historians. The ethnic nationalism which on one hand is a cultural revival but on the other promotes a hate agenda, is dangerous and antithetical to the inter group relations and unity of the North Central of Nigeria.

Ethnic hate, the idea that some ethnic nationalities do not belong or have indigenous roots in a state, has been responsible for some of the modern genocide and massacre in the history of modern Nigeria.

For political and security reasons, there is scanty research in this regard, the study of modern genocide backed by state action. Or where such research exist, it is often play down and watered as inter group conflicts and violent hostilities that should be treated with kids gloves and palliatives. This liberal and pessimistic approach to conflict management has been a responsible factor in the decimal reoccurrence of violent ethnic conflicts of the North Central States. The Liberal approach to conflict management, looks at the symptoms instead of the treatment of the disease.

Ethnocentrism is both an African and Nigerian reality that over time and space has been fueled and exploited by the ruling political class and elites. It is one of critical challenge of nation building in Africa that appears to be a curse of a continent and people.

All nations of the world have their share of the nightmare of ethnic and racial bigotry at one point or the other in their national history and transformation.

In the United States of America, it was dubbed the race question in the post emancipation era, the politics of the color line as William Dubios described the racial tension and phenomenon of his prevailing age and society. The race question sparked many reactions including the establishment of societies and organizations for the protection of the African American as well as the defence of the fundamental civil rights of the “American Negro”.

One of such initiative adopted by the State in America which was aimed at the improvement of the welfare and wellbeing of the African American as as his integration into main stream society was the establishment of the Bureau For Freed Men on race relations. The Bureau as a Federal institution was designed for the reconciliation of the inequality and segregation of the African American inorder for him to access equitable development and national resources, but, more importantly, political representation at both state and national level.

Subsequently, the Bureau came up with a number of proactive programmes and policies including the Affirmative Action as well as Federal Character Quota Systems that ensured the equitable and just integration of African Americans in main stream society and politics.

In recent years, Nigeria has established some regional frameworks that can translate into the creation of a Bureau for Ethnic Relations. One of such regional framework is the establishment of the North Central Development Commission by President Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

The Development Commission if strategically placed and positioned, can create a Bureau For Ethnic Relations that will help promote and reconcile inter-ethnic relations and development within the North Central of Nigeria.

I am limited as to the mandate of the commission interms development and the transformation of the North Central of Nigeria.

If the commission suffers from a deficit to manage ethnic relations along the lines of affirmative action and federal character principle, then, the federal government should as a matter of social priority establish an Bureau For Ethnic Relations of the six geopolitical units of Nigeria.

Let me end this write up by using the words of William Dubios that the challenge of Nigeria in the twenty first century is that of ethnic relations, it is that of the ethnic content, that of fairer skin races to that of the dark skin races.

Prof. Uji Wilfred is from the Department of History and International Studies, Federal University of Lafia

Education

Varsity Don Advocates Establishment of National Bureau for Ethnic Relations, Inter-Group Unity

By David Torough, Abuja

A university scholar, Prof. Uji Wilfred of the Department of History and International Studies, Federal University of Lafia, has called on the Federal Government to establish a National Bureau for Ethnic Relations to strengthen inter-group unity and address the deep-seated ethnic tensions in Nigeria, particularly in the North Central region.

Prof.

Wilfred, in a paper drawing from years of research, argued that the six states of the North Central—Kwara, Niger, Kogi, Benue, Plateau, and Nasarawa share long-standing historical, cultural, and economic ties that have been eroded by arbitrary state boundaries and ethnic politics.According to him, pre-colonial North Central Nigeria was home to a rich mix of ethnic groups—including Nupe, Gwari, Gbagi, Eggon, Igala, Idoma, Jukun, Alago, Tiv, Birom, Tarok, Angas, among others, who coexisted through indigenous peace mechanisms.

These communities, he noted, were amalgamated by British colonial authorities under the Northern Region, first headquartered in Lokoja before being moved to Kaduna.

He stressed that state creation, which was intended to promote minority inclusion, has in some cases fueled exclusionary politics and ethnic tensions. “It is historically misleading,” Wilfred stated, “to regard certain ethnic nationalities as mere tenant settlers in states where they have deep indigenous roots.”

The don warned that such narratives have been exploited by political elites for land grabbing, ethnic cleansing, and violent conflicts, undermining security in the sub-region.

He likened Nigeria’s ethnic question to America’s historic “race question” and urged the adoption of structures similar to the Freedmen’s Bureau, which addressed racial inequality in post-emancipation America through affirmative action and equitable representation.

Wilfred acknowledged the recent creation of the North Central Development Commission by President Bola Tinubu as a step in the right direction, but said its mandate may not be sufficient to address ethnic relations.

He urged the federal government to either expand the commission’s role or create a dedicated Bureau for Ethnic Relations in all six geo-political zones to foster reconciliation, equality, and sustainable development.

Quoting African-American scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, Prof. Wilfred concluded that the challenge of Nigeria in the 21st century is fundamentally one of ethnic relations, which must be addressed with deliberate policies for unity and integration.

OPINION

The Pre-2027 Party gold Rush

By Dakuku Peterside

The 2027 general elections are fast approaching, and Nigeria’s political landscape is undergoing a rapid transformation. New acronyms, and freshly minted party logos are emerging, promising a new era of renewal and liberation.To the casual observer, this may seem like democracy in full bloom — citizens exercising their right to association, political diversity flourishing, and the marketplace of ideas expanding.

However, beneath this surface, a more urgent reality is unfolding. The current rush to establish new parties is less about ideological conviction or grassroots movements and more about strategic positioning, bargaining leverage, and transactional gain.It is the paradox of Nigerian politics: proliferation as a sign of vitality, and as a symptom of democratic fragility. With 2027 on the horizon, the political air is electric, not with fresh ideas, but with a gold rush to create new political parties.Supporters call it the flowering of democracy. But scratch the surface and you will see something else: opportunism dressed as pluralism. This is not just politics; it is political merchandising. Parties are being set up like small businesses, complete with negotiation value, resale potential, and short-term profit models. Today, Nigeria has 19 registered political parties, one of the highest numbers in the world behind India (2,500), Brazil (35), and Indonesia (18).History serves as a cautionary tale in this context. Whenever Nigeria has embraced multi-party politics, the electoral battlefield has eventually narrowed to a contest between two main poles. In the early 1990s, General Ibrahim Babangida’s political transition programme deliberately engineered a two-party structure by decreeing the creation of the National Republican Convention (NRC) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP).His justification was rooted in the observation — controversial but not entirely unfounded — that Nigeria’s political psychology tends to gravitate toward two dominant camps, thereby simplifying voter choice and fostering more stable governance. Pro-democracy activists condemned the move as state-engineered politics, but over time, the pattern became embedded.When Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1999, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) emerged as the dominant force, facing off against the All People’s Party (APP) and Alliance for Democracy (AD) coalition. The 2003 and 2007 elections pitted the PDP against the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP); in 2011, the PDP contended with both the ANPP and the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC).By 2015, the formation of the All Progressives Congress (APC) — a coalition of the CPC, ANPP, Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), and a faction of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) — restored the two-bloc dynamic. This ‘two-bloc dynamic’ refers to the situation where most of the political power is concentrated within two main parties, leading to a less diverse and competitive political landscape. Even when dozens of smaller parties appeared on the ballot, the real contest was still a battle of two heavyweights.And yet, here we are again, with Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) registering nineteen parties but facing an avalanche of new applications — 110 by late June, swelling to at least 122 by early July. This surge is striking, especially considering that after the 2019 general elections, INEC deregistered seventy-four parties for failing to meet constitutional performance requirements — a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in 2021.That landmark ruling underscored that party registration is not a perpetual license; it is a privilege conditioned on meeting electoral benchmarks, such as a minimum vote share and representation across the federation. The surge in party formation could potentially lead to a more complex and fragmented electoral process, making it harder for voters to make informed decisions and for smaller parties to gain traction.So, what explains the surge in the formation of new parties now? The reasons are not mysterious. Money is the bluntest answer, but it is woven with other motives. For some, creating a party is a strategic move to position themselves for negotiations with larger parties — trading endorsements, securing “alliances,” and even extracting concessions like campaign funding or political appointments.Others set up “friendly” parties designed to dilute opposition votes in targeted constituencies, often indirectly benefiting the ruling party. Some political entrepreneurs build parties as personal vehicles for regional ambitions or as escape routes from established parties, where rival factions have captured the leadership.Some are escape pods for politicians frozen out of the ruling APC’s machinery. There is also a genuine democratic impulse among certain groups to create platforms for neglected ideas or underrepresented constituencies. But the transactional motive often eclipses these idealistic efforts, leaving most new parties as temporary instruments, rather than enduring institutions.The democratic consequences of this kind of proliferation are profound. On one hand, political pluralism is a constitutional right and an essential feature of democracy. On the other hand, too many weak, poorly organised parties can fragment the opposition, confuse voters, and degrade the quality of political competition.Many of these micro-parties lack ward-level presence, a consistent membership drive, and ideological coherence. Their manifestos are often generic, interchangeable documents crafted to meet registration requirements, rather than to present a distinct policy vision. On election-day, their presence on the ballot can be more of a distraction than a contribution, and after the polls close, many vanish from public life until the next cycle of political registration. This is not democracy — it is ballot clutter.This is not uniquely Nigerian. In India, a few thousands registered parties exist, yet only a fraction of them is active or competitive at the state or national level. Brazil, notorious for its highly fragmented legislature, has struggled with unstable coalitions and governance deadlock; even now, it is reducing the number of effective parties.Indonesia allows many parties to register but imposes a parliamentary threshold — currently four per cent of the national vote — to limit legislative fragmentation. These examples, along with others from around the world, suggest that plurality can work, but only when paired with guardrails: stringent conditions for registration, clear criteria for participation, performance-based retention, and an electoral culture that rewards sustained engagement over fleeting visibility.Nigeria already has a version of this in place, courtesy of INEC’s power to deregister. We deregistered seventy-four parties in 2020 for failing to meet performance standards, and five years later, we are sprinting back to the same cliff.Yet, loopholes remain especially, and the process is reactive rather than proactive. Registration conditionalities are lax. This is where both INEC and the ruling APC must shoulder greater responsibility. The need for electoral reform is urgent, and it is time for all stakeholders to act.For INEC, the task is to strengthen its oversight by tightening membership verification, enhancing financial transparency, and expanding its geographic spread requirements, as well as introducing periodic revalidation between election cycles.For the ruling party, the challenge lies in upholding political ethics: resisting the temptation to exploit party proliferation to splinter the opposition for short-term gain. A strong ruling party in a democracy wins competitive elections, not one that manipulates the field to run unopposed. Strong democracy requires a credible opposition, not a scattering of paper platforms that cannot even win a ward councillor seat.Here is the truth: this system needs reform. Reform doesn’t mean closing the democratic space, but making it meaningful and orderly. Democracy must balance full freedom of association with the need for order. While freedom encourages many parties, order requires limiting their number to a manageable level.For example, Nigeria could require parties to have active structures in two-thirds of states, a verifiable membership, and annual audited financials. Parties failing to win National Assembly seats in two consecutive elections could lose registration.The message to new parties is clear: prove you’re more than just a logo and acronym. Build lasting movements — organise locally, offer real policies alternatives, and stay engaged between elections.Democracy is a contest of ideas, discipline, and trust. If the 2027 rush is allowed to run unchecked, we will end up with the worst of both worlds — a crowded ballot and an empty choice. Mergers should be incentivised through streamlined legal processes and possibly electoral benefits, such as ballot priority or increased public funding. At the same time, independent candidates should be allowed more room to compete, ensuring that reform does not entrench an exclusive two-party cartel.Ultimately, the deeper issue here is the erosion of public trust. Nigerians have no inherent hostility to new political formations; what they distrust are political outfits that emerge in the months leading up to an election, strike opaque deals, and disappear without a trace. Politicians must resist the temptation to treat politics as a seasonal business opportunity and instead invest in it as a long-term public service.As 2027 approaches, Nigeria stands at a familiar but critical juncture. The country can indulge the frenzy — rolling out yet another logo, staging yet another press conference, promising yet another “structure” that exists mainly on paper. Or it can seize this moment to rethink how political competition is structured: open but disciplined, plural but purposeful, competitive but coherent.Fewer parties will not automatically make Nigeria’s democracy healthier. But better parties — rooted in communities, committed to clear policies, and resilient beyond election season — just might. And that is a choice within reach, if those who hold the levers of power are willing to leave the system stronger than they found it.Dakuku Peterside, a public sector turnaround expert, public policy analyst and leadership coach, is the author of the forthcoming book, “Leading in a Storm”, a book on crisis leadership.