OPINION

Why Bola Tinubu Must Never be Nigeria’s President

By Festus Adedayo

I was at the Alausa Governor’s Office in Lagos. Accessing the governor was like seeking a needle in a haystack. His Press Secretary had sent word up that an irritant interloper had come to ferret a response to a news magazine’s damming exposé on the governor.

After hours of waiting, a commissioner (name withheld) sauntered in and met me where I sat immovably like Mount Kilimanjaro. “You can’t write that story,” he began in a steely voice laced with a veiled threat. “Go back to Ibadan. We will talk to your boss.” That was how the story never saw the light of the day.The Nigerian Tribune, of which I was the Features Editor during this period, had sent me in pursuit of the facts or fiction surrounding the news magazine’s report.

The principal of that ancient school, Government College Ibadan (GCI), had suddenly gone AWOL then, becoming as incommunicado and inaccessible as the proverbial excrement of the masquerade. Through the grapevine, there was an allegation that Alhaji Lam Adesina, the governor of Oyo State at the time, had ordered that all data of the school’s attendees during the period of Governor Bola Tinubu’s supposed attendance of GCI be brought to him in the Government House, where they were then placed under lock and key. The media that were seeking the corroboration or converse of those claims, went after the Principal of GCI. He had disappeared into thin air. Perhaps, a one-on-one interview with the governor would do?In 1999, one Dr Waliu Balogun wrote a petition against Tinubu, leveling a number of damning allegations that bordered on fraudulent claims of educational attainments. Among other things, he accused Tinubu of lying in an affidavit attached to his Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) form that he lost his degree certificates while he was on exile between 1994 and 1998. The news magazine later published those details in a gripping exposé which left sour tastes in the mouth.

One after the other, all of Tinubu’s claims, sworn to under oath in the Form CF001 he filled with INEC, were shredded to smithereens by the magazine’s story. St. Paul’s School, Aroloya, Lagos, which he claimed to have attended, was found never to have existed, in the investigative reporting of the magazine, just as his name was conspicuously missing from the records of the Government College, Ibadan, which he claimed to have attended between 1965 and 1968. Indeed, GCI’s alumni association, the Old Boys of the school, debunked the claim of having him as a member. So also was Tinubu’s claim to have attended Richard Daley College, Chicago, between 1969 and 1971. Punctured also were the governor’s claims of being a student of the University of Chicago in the U.S. between 1972 and 1976, as well as obtaining a B.Sc degree in Economics from the university. A request to those institutions for affirmation of Tinubu’s studentship by the magazine came up with a resounding ‘No.’ Till date, in spite of his having vanquished the legal principalities spearheaded by Chief Gani Fawehinmi (SAN), with the Supreme Court voiding Fawehinmi on technical grounds, none of Tinubu’s classmates, schoolmates or even teachers, has come out in public to counter the facts of the legal behemoth erected against him.

Four years later, in 2003, it was time for Tinubu to fill the Form CF001 again, in pursuit of his second term bid. His enemies who were waiting for him to make those claims again were dazed when they saw what the governor filled. In all the columns, the gentleman simply filled NOT APPLICABLE – Primary School: Not Applicable; Secondary School: Not Applicable and; University: Not Applicable! Could that have meant that the man never attended any school?

Tinubu was not alone. Rife as expectations were from the new-found Nigerian republic in 1999, like alligators, renowned for the incredible nasal power of smelling a drop of blood, even in ten gallons of water, Nigerians smelt crises in the cache of scandals that involved newly elected office holders of the republic. Less than three months after commencement of the Fourth Republic, Nigeria began to manifest noticeable cracks. It took political scientists and students of Marxian dialectics to allay our fears and tell us that those cracks were curative, self-correcting and akin to the Marxist postulation of thesis and antithesis which, when they jam, produce a synthesis.

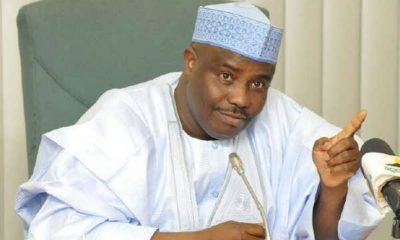

In a quick succession of messy, damming scandals, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Salisu Buhari; Senate President, Evan(s) Enwerem and Bola Tinubu got entangled in seismic, roiling scandals of identity misappropriation, subversion of their oaths of office and perversion of truth. While the earlier two were swept away by the typhoon of the crises, Tinubu not only survived the ignominy, to spite the allegations, he is today one of the top three most consequential and powerful Nigerians alive, and a presidential office aspirant to boot.

Salisu Buhari, the affable and young Speaker of the lower parliament had just then been unraveled by the media as an age inflator and certificate forger. Hitherto a Kano-based businessman, Buhari had made an entry into politics, but barely two weeks after being sworn into office, the now rested news magazine, TheNews, in its February 16, 1999 edition, published details of his age and certificate forgery. The magazine wrote that he was actually born in 1970 and not in 1963 as he had claimed.

Again, TheNews put a lie to Buhari’s claim of having graduated from the University of Toronto, stating that he not only did attend the school, the mandatory youth service he claimed to have undergone at Standard Construction in Kano was equally fiction. On July 23, 1999, like a rain-soaked squirrel, Buhari was contrite, disgraced and admitted all the allegations. “I apologise to you. I apologise to the nation. I apologise to my family and friends for all the distress I have caused them. I was misled in error by a zeal to serve the nation. I hope the nation will forgive me and give me the opportunity to serve again,” he murmured as he resigned from the House. He was subsequently convicted of certificate forgery, sentenced to two years in prison but was pardoned by President Olusegun Obasanjo.

Senate President, Evan Enwerem, was to kiss the canvass a little while after. In the race for the Senate presidency, he had sidestepped his closest sprinter rival, Chuba Okadigbo, for the office by 66 to 43 votes. Shortly after his ascension in 1999, Enwerem was shoved into the sieve, and scrutinised on the allegation of an identity opacity. He was held up on the fire-spitting wire gauze for the falsification of his name. A ball-fire of controversy erupted on whether Enwerem’s real name was Evan or Evans. In the melee, on November 18, 1999, his ouster, spearheaded by Okadigbo and his allies, became a fait accompli.

Between his consequential emergence on the political turf of Nigeria in 1999 and now, only an armchair, analytical yokel will underrate or belittle Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s awesome and colonising genius in Nigerian politics. He became so consequential that some translucent analyses compare him to the sage, Obafemi Awolowo. It appears that immediately he got away from the drowning tidal waves of that identity theft legal tango and the lacerating fisticuffs of his numerous political adversaries, Tinubu tightened his muscles on the political levers of Lagos, a State which had always been the microcosm of Nigeria since it became the federal capital of independent Nigeria in 1960. He saw how the almighty power of the media, like a mammoth whale, almost succeeded in capsizing his ship of state and political career.

Rising from the ashes of the crises, Tinubu encircled his claw-like fists on the media, meandering himself into its total corpus and essentialising himself in its operations. While English crime thriller writer, René Lodge Brabazon Raymond, popularly known as James Hadley Chase, says that fear opens the wallets of the rich, Tinubu’s street chemistry, which he deploys, says that licit and illicit favours, prebends and perks, imprison consciences and arrest captives faster than the glue gum traps mice. Unconscionably, Tinubu waves these aces with the magisterial clinicality of a professional executioner, succeeding in the process in harvesting a huge cache of political, media, government, judicial, corporate, etcetera clienteles inside his massive pouch.

The truth is that since 1960, seldom has Nigeria had a political aficionado who has deployed the genius of the streets in the service of politics, as Bola Tinubu has done. Scarcely can anybody have the mis/fortune of encountering him without becoming a captive of his cash influence. Someone once said that even the god of Mammon would be envious of Tinubu’s sagacity in deploying its essence as a weapon.

Within the span of his Lagos governorship of eight years, from someone who those who knew him said was passably well-to-do, Tinubu grew a monstrous wealth, such that a 2015 back page opinion piece in The Sun newspaper claimed he owned almost half of Lagos and urged Buhari to clone the Vladimir Putin method with which the Russian president neutralised drug czars who funded his presidential emergence. Within this period, Tinubu also acquired a humongous political influence within Lagos and outside, that could rank aside those of the Pharaohs and emperors of old. In 2007, an ex-governor, who witnessed the miasma of power flakes encircling him as he arrived the Lagos airport, jealously told me that it was godlike.

Superficial analyses of Tinubu claim that his vice-hold grip on Lagos can be found in his ability to “build” and plant people in state and national offices, while sustaining a linear pattern of succession. This, such analysts claim, reflects his sagacity. Those who know the modus operandi of this power retention system however put a lie to it. To them, deep beneath it is an opaque, yet fastidiously maintained and pervasively sustained system of mega corruption and the perpetuation of self hegemony, through a carefully mastered mind-coercion, which is promoted by a cultic abidance to an oath of allegiance.

Those who see Tinubu’s strength in his fluid recruitment of aides, should also be able to answer why he suffers the huge casualty of his investment in such persons? Could it be that he uses them as indentured viceroys? Or that the rebellion we see from them is an attempt to set themselves free of his hold? From Babatunde Fashola, Muiz Banire, Akinwumi Ambode to Rauf Aregbesola, and many others, there must be a single thread that unifies Tinubu’s foot soldiers’ rebellion against him. Unfortunately for Tinubu, this same set of soldiers, knowing the secrets of the sustenance of their power machine, are today against his emergence as Nigeria’s president and will willingly supply the fire that will incinerate his ambition. In Yorubaland today, apart from Lagos and Osun States, which APC governor can Tinubu claim to be under him?

If nothing else, the controversy provoked by Chief Bisi Akande’s My Participations unraveled the mythic notion that Tinubu promotes his aides to the top for the love of country. Back and forth arguments, especially about Vice President Yemi Osinbajo’s nomination in 2015, revealed that not only is the Lagos landlord obsessed with the self alone, the ascension of others in his loop is secondary and subordinated to the personal interest. The world saw that Tinubu grudgingly acceded to Osinbajo’s candidacy, only when his personal interest hit the rocks.

Last week, however, Bola Tinubu paid a visit to President Buhari, a few hours after the latter granted an incoherent interview where he claimed that if he named his successor, the fellow could be assassinated. A content analysis of the president’s statement must have revealed to Tinubu that he could never have been the one Buhari was referring to. Tinubu must know that Buhari knows that a plan to murder Death would be easier done than assassinating Nigeria’s Mafia don, the Capo dei capi himself.

The most mis-recommending criterion against a Tinubu presidency is that, in mental depth, the Lagos Landlord is just a whiff higher than Muhammadu Buhari. Remove the cockney accent he feebly mimics, you will find out that most times, his extempore speeches lack coherence, logic and verve.

Counter-arguments have been proffered against the school of thought that says Tinubu’s ultra-stupendous wealth should recommend him against vying for the Nigerian presidency. You will recollect that the military apparatchik argued along this line against an MKO Abiola presidency. Abiola, they said, was as wealthy as to grant Nigeria loans. Weak as the argument was, it is strong in Tinubu’s disfavour, for its moral and deleterious implications. While the world knew that Abiola’s wealth was procured from international dealings, especially in ITT, Tinubu is said to own a pie in virtually every sector of the Nigerian economy, ranging from oil, steel, finance (tax), airline, real estate, to the media, and you name it. These are all operated in names of shells and proxies. In all these, as the Americans say, we can see the bucks but not the shop. What morality will Nigeria be preaching by having a president of such opaque composition and disposition?

Either real or imagined, it is said that the only thing that is real about Tinubu is his person and that every other ascription on him is a borrowed robe. He has not come in the open to effectively disclaim the allegation that his name is not his name; that the parents he claimed were not his; that the certificates he claimed to be his are not and that the schools he claimed to have attended, didn’t know him. I don’t know a baggage bigger than this for a country like Nigeria that is struggling to sell herself to the world, to now have its president burdened by this pernicious pedigree.

With the calamity that the Buhari presidency has posed to Nigeria, it will be more calamitous to have a Tinubu as his successor. Governing Nigeria is not all about identifying surrogates who will man critical political offices for future political gains. Nigeria needs a cerebral, healthy, comparatively morally overboard president, a man – borrowing from Oscar Wilde’s description of his gay partner friend, Sir Alfred Douglas in De Profundis – who is not a man for whom the gutter and all that is in it fascinates.

One would have expected Tinubu to heed the counsel of Apala music icon, Ayinla Omowura. Omowura must have had in mind leaders who are heavy-laden, burdened by baggage of their past, when he counseled that, as all shrubs and leaves in the forest should not be the predilection of a herbalist seeking curative herbs; not all palm trees in the forest should excite the palm-wine tapper either. In Yoruba, he expressed this as, “gbogbo ewe ko l’ojawe nja; gbogbo ope ko l’onigba ngun.” Sagacious leaders who carry stupendous moral baggage of the Tinubu hue should know the forests they ought to venture into.

The forests of presidential contest that the Lagos Landlord is about to venture into is what same Omowura, in his vinyl, referred to as “igbo odaju” – the forest of the heartless, the hard carapace-hearted hunters. At least not anyone who does not have the benefit of a real mother – a real mother’s prayers are like magic, steeped in mystical and metaphysical powers. Anyone, said Omowura, who does not have a real mother who can provide the protection of witchcraft for them, should not venture into igbo odaju. Never! Abraham Lincoln, father of the American nation, also alluded to this when he said, “I remember my mother’s prayers and they have always followed me. They have clung to me all my life.”

Some Yoruba lament what they call the predilection of the Yoruba for pulling themselves down. This piece would be their perfect example. It is thinking like this that has condemned Nigeria to stagnation. The truth is, the Yoruba are very proud of their pedigree and wear it like a lapel on their sleeves. So how can the same Yoruba who have preached moral uprightness to the rest of the world for centuries, now queue behind a man who cannot point his right hand at his father’s homestead? Let the rest of Nigeria be rotten eggs. The Yoruba will still underscore the societal purity. It should gladden us that the Yoruba are the ones revealing the maggots in their home so that when they expose the maggots in others, they will occupy a higher moral ground. It is better for the Yoruba not to lift a presidential leg forward than lift one that is riddled with a festering and putrid sore. In any case, what Nigeria needs is a president that is a leader who is not crippled by ill health and is adequately schooled in the nuances of 21st century solutions to our self-inflicted, existential challenges.

Since independence in 1960, six ‘major’ Yoruba sons have attempted a shot at Nigeria’s civilian presidency (excluding fringe aspirants of Babangida’s political guinea-pig era). They are Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Alhaji Lateef Jakande, Chiefs Abiola, Bola Ige, Olu Falae and Olusegun Obasanjo. If Tinubu carries through his recent declaration, he will be joining this pantheon. Of this lot, Tinubu would be the only one whose pedigree is shrouded in a miasma of dubiety.

Yoruba will totally support Tinubu in his presidency dream if he agrees to fill in the INEC forms all those claims he made of his roots in 1999. He must fill in the 2023 Form CF001 St. Paul’s School, Aroloya, Lagos, as his primary school; Government College, Ibadan; Richard Daley College, Chicago and the University of Chicago as his alma maters, without Senator Tokunbo Afikuyomi swearing on oath that he filled them for him by proxy.

Festus Adedayo is an Ibadan-based journalist.

OPINION

The Pre-2027 Party gold Rush

By Dakuku Peterside

The 2027 general elections are fast approaching, and Nigeria’s political landscape is undergoing a rapid transformation. New acronyms, and freshly minted party logos are emerging, promising a new era of renewal and liberation.To the casual observer, this may seem like democracy in full bloom — citizens exercising their right to association, political diversity flourishing, and the marketplace of ideas expanding.

However, beneath this surface, a more urgent reality is unfolding. The current rush to establish new parties is less about ideological conviction or grassroots movements and more about strategic positioning, bargaining leverage, and transactional gain.It is the paradox of Nigerian politics: proliferation as a sign of vitality, and as a symptom of democratic fragility. With 2027 on the horizon, the political air is electric, not with fresh ideas, but with a gold rush to create new political parties.Supporters call it the flowering of democracy. But scratch the surface and you will see something else: opportunism dressed as pluralism. This is not just politics; it is political merchandising. Parties are being set up like small businesses, complete with negotiation value, resale potential, and short-term profit models. Today, Nigeria has 19 registered political parties, one of the highest numbers in the world behind India (2,500), Brazil (35), and Indonesia (18).History serves as a cautionary tale in this context. Whenever Nigeria has embraced multi-party politics, the electoral battlefield has eventually narrowed to a contest between two main poles. In the early 1990s, General Ibrahim Babangida’s political transition programme deliberately engineered a two-party structure by decreeing the creation of the National Republican Convention (NRC) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP).His justification was rooted in the observation — controversial but not entirely unfounded — that Nigeria’s political psychology tends to gravitate toward two dominant camps, thereby simplifying voter choice and fostering more stable governance. Pro-democracy activists condemned the move as state-engineered politics, but over time, the pattern became embedded.When Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1999, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) emerged as the dominant force, facing off against the All People’s Party (APP) and Alliance for Democracy (AD) coalition. The 2003 and 2007 elections pitted the PDP against the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP); in 2011, the PDP contended with both the ANPP and the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC).By 2015, the formation of the All Progressives Congress (APC) — a coalition of the CPC, ANPP, Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), and a faction of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) — restored the two-bloc dynamic. This ‘two-bloc dynamic’ refers to the situation where most of the political power is concentrated within two main parties, leading to a less diverse and competitive political landscape. Even when dozens of smaller parties appeared on the ballot, the real contest was still a battle of two heavyweights.And yet, here we are again, with Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) registering nineteen parties but facing an avalanche of new applications — 110 by late June, swelling to at least 122 by early July. This surge is striking, especially considering that after the 2019 general elections, INEC deregistered seventy-four parties for failing to meet constitutional performance requirements — a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in 2021.That landmark ruling underscored that party registration is not a perpetual license; it is a privilege conditioned on meeting electoral benchmarks, such as a minimum vote share and representation across the federation. The surge in party formation could potentially lead to a more complex and fragmented electoral process, making it harder for voters to make informed decisions and for smaller parties to gain traction.So, what explains the surge in the formation of new parties now? The reasons are not mysterious. Money is the bluntest answer, but it is woven with other motives. For some, creating a party is a strategic move to position themselves for negotiations with larger parties — trading endorsements, securing “alliances,” and even extracting concessions like campaign funding or political appointments.Others set up “friendly” parties designed to dilute opposition votes in targeted constituencies, often indirectly benefiting the ruling party. Some political entrepreneurs build parties as personal vehicles for regional ambitions or as escape routes from established parties, where rival factions have captured the leadership.Some are escape pods for politicians frozen out of the ruling APC’s machinery. There is also a genuine democratic impulse among certain groups to create platforms for neglected ideas or underrepresented constituencies. But the transactional motive often eclipses these idealistic efforts, leaving most new parties as temporary instruments, rather than enduring institutions.The democratic consequences of this kind of proliferation are profound. On one hand, political pluralism is a constitutional right and an essential feature of democracy. On the other hand, too many weak, poorly organised parties can fragment the opposition, confuse voters, and degrade the quality of political competition.Many of these micro-parties lack ward-level presence, a consistent membership drive, and ideological coherence. Their manifestos are often generic, interchangeable documents crafted to meet registration requirements, rather than to present a distinct policy vision. On election-day, their presence on the ballot can be more of a distraction than a contribution, and after the polls close, many vanish from public life until the next cycle of political registration. This is not democracy — it is ballot clutter.This is not uniquely Nigerian. In India, a few thousands registered parties exist, yet only a fraction of them is active or competitive at the state or national level. Brazil, notorious for its highly fragmented legislature, has struggled with unstable coalitions and governance deadlock; even now, it is reducing the number of effective parties.Indonesia allows many parties to register but imposes a parliamentary threshold — currently four per cent of the national vote — to limit legislative fragmentation. These examples, along with others from around the world, suggest that plurality can work, but only when paired with guardrails: stringent conditions for registration, clear criteria for participation, performance-based retention, and an electoral culture that rewards sustained engagement over fleeting visibility.Nigeria already has a version of this in place, courtesy of INEC’s power to deregister. We deregistered seventy-four parties in 2020 for failing to meet performance standards, and five years later, we are sprinting back to the same cliff.Yet, loopholes remain especially, and the process is reactive rather than proactive. Registration conditionalities are lax. This is where both INEC and the ruling APC must shoulder greater responsibility. The need for electoral reform is urgent, and it is time for all stakeholders to act.For INEC, the task is to strengthen its oversight by tightening membership verification, enhancing financial transparency, and expanding its geographic spread requirements, as well as introducing periodic revalidation between election cycles.For the ruling party, the challenge lies in upholding political ethics: resisting the temptation to exploit party proliferation to splinter the opposition for short-term gain. A strong ruling party in a democracy wins competitive elections, not one that manipulates the field to run unopposed. Strong democracy requires a credible opposition, not a scattering of paper platforms that cannot even win a ward councillor seat.Here is the truth: this system needs reform. Reform doesn’t mean closing the democratic space, but making it meaningful and orderly. Democracy must balance full freedom of association with the need for order. While freedom encourages many parties, order requires limiting their number to a manageable level.For example, Nigeria could require parties to have active structures in two-thirds of states, a verifiable membership, and annual audited financials. Parties failing to win National Assembly seats in two consecutive elections could lose registration.The message to new parties is clear: prove you’re more than just a logo and acronym. Build lasting movements — organise locally, offer real policies alternatives, and stay engaged between elections.Democracy is a contest of ideas, discipline, and trust. If the 2027 rush is allowed to run unchecked, we will end up with the worst of both worlds — a crowded ballot and an empty choice. Mergers should be incentivised through streamlined legal processes and possibly electoral benefits, such as ballot priority or increased public funding. At the same time, independent candidates should be allowed more room to compete, ensuring that reform does not entrench an exclusive two-party cartel.Ultimately, the deeper issue here is the erosion of public trust. Nigerians have no inherent hostility to new political formations; what they distrust are political outfits that emerge in the months leading up to an election, strike opaque deals, and disappear without a trace. Politicians must resist the temptation to treat politics as a seasonal business opportunity and instead invest in it as a long-term public service.As 2027 approaches, Nigeria stands at a familiar but critical juncture. The country can indulge the frenzy — rolling out yet another logo, staging yet another press conference, promising yet another “structure” that exists mainly on paper. Or it can seize this moment to rethink how political competition is structured: open but disciplined, plural but purposeful, competitive but coherent.Fewer parties will not automatically make Nigeria’s democracy healthier. But better parties — rooted in communities, committed to clear policies, and resilient beyond election season — just might. And that is a choice within reach, if those who hold the levers of power are willing to leave the system stronger than they found it.Dakuku Peterside, a public sector turnaround expert, public policy analyst and leadership coach, is the author of the forthcoming book, “Leading in a Storm”, a book on crisis leadership.OPINION

Call for National Youth Career Development Initiative

By Blessing Adeoti

Nigerian youths are intelligent and hardworking, but very few have a solid career development plan. It doesn’t matter whether a student graduates with first-class honours or shows great potential; most focus on just one goal: earning a degree or certificate from a higher institution and then seeking job opportunities.

The main issues are the lack of available jobs, and nowhere in the world is it necessary for the government to guarantee employment for everyone. Moreover, not every student who attends a higher institution needs to follow such a path.Most people may be better suited to alternative routes, such as technical or vocational training, to develop competent professionals in industries that lack sufficient specialised expertise, including electricians, carpentry, plumbing, welding, mechanics, computer skills, and others. These are skills in high demand that will enable the youth to contribute meaningfully to the economy, even as entrepreneurs.Although President Bola Tinubu’s administration is trying to revive the technical colleges, what orientation do the students have to embrace the unique opportunities? Should we blame the youths for lacking this foresight? No! The root of the problem lies in the absence of structured career counselling in Nigeria’s educational system.Nigerian youths face the challenges of navigating the uncertainty in career pursuits. This is not because they lacked aspirations, but rather due to the near-total absence of a functional career counselling system within the Nigerian education sector. Nigeria’s career counselling vacuum dates to the colonial education system, which was mainly designed to produce clerks, administrators, and workers for the service sector. The focus was never on helping students discover their strengths or guiding them toward career paths that could help them achieve their full potential.After independence, the National Policy on Education of 1977, revised in 2013, mandated the introduction of guidance and counselling services in schools, but implementation has been significantly inadequate. Globally, the economic and job realities have changed. As a university lecturer, I have seen firsthand the struggles many students face, yet not one has ever had experience with a career guide or counsellor.In 2020, the Institute of Counselling in Nigeria revealed that only 15 per cent of secondary schools have functional counselling units, and many of these are staffed by untrained personnel. This neglect has produced a generation of aimless graduates, unemployment, underemployment, and skills mismatches. It signals a disconnect between the education system and the labour market, as graduates are often unprepared for the skills required in today’s economy.Economically, the World Bank estimates that youth unemployment costs Nigeria billions in lost GDP annually. The psychological effects are equally devastating. Career indecision is linked to anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression among young Nigerians, according to a 2021 study from the University of Ibadan, which found that many students trapped in unsuitable career paths experienced significant psychological distress.Socially, this has contributed to increased crime, cultism, extremism and terrorism across the country. Nigeria’s crime rate, ranked 7.28 out of 10 globally, is partly fuelled by jobless youth seeking alternative livelihoods.There is hope for change as President Bola Tinubu’s administration has shown a genuine commitment to supporting Nigerian youth. The President’s Renewed Hope agenda for education, including the Nigeria Education Loan Fund and the revitalisation of Nigeria’s technical and vocational colleges, is commendable.However, these efforts risk falling short without the addition of a well-structured national youth career development programme. There are proven models from around the world that Nigeria can adapt to address this challenge. For example, Finland, renowned for its world-class education system, places a strong emphasis on career guidance.From an early age, Finnish students receive career counselling as part of their school curriculum. Trained career counsellors work closely with students to identify their strengths, interests, and goals. Similarly, Singapore implemented the education and career guidance programme, which aligns student aspirations with workforce needs, helping the country maintain youth unemployment below 5 per cent (Singapore Ministry of Education, 2024).In Australia, the National Career Education Strategy prepares young people for the future of work by integrating career education into the school curriculum, emphasising transferable skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability.President Tinubu’s administration can rebuild Nigeria’s system by launching an aggressive youth career development initiative that ensures the President’s educational reforms translate into tangible outcomes.Such an initiative would equip students with the clarity and direction needed to fulfil both their personal aspirations and national economic needs. This is about giving young Nigerians the tools, confidence, and clarity to chart their career developmental paths.With renewed focus and investment, the government now has a real chance to correct past mistakes and help young Nigerians build brighter, more diverse career futures. There are many ideas for structures that could produce excellent results within a year, but Nigeria needs someone, or a team of passionate individuals, to turn them into reality.I recommend that President Tinubu appoint a special adviser for the National Youth Career Development Initiative to avoid the unnecessary bureaucracy that slows down many good initiatives. The special adviser must be an innovative thinker, a visionary leader with empathy and a deep understanding of Nigeria’s youth and job market dynamics, and a passion for empowering the next generation.The candidate would advise the President on a viable initiative for a national youth career development programme and work with other stakeholders. The government must take the lead by prioritising career counselling in its education policies and enforcing the establishment of functional guidance units in all schools.Dr Adeoti writes from Hong Kong via badeoti3@gmail.comOPINION

A Tale of Two Reforms: Why Nigeria Must Not Blink

By O’tega ‘The Tiger’ Ogra

Economic reform is never painless. Every nation that has had to correct profound distortions has faced the same choice: take the hard medicine early, or delay and pay much more later. In times of public frustration, it is tempting to reach for the “gentle” option (the idea of gradual change), being pushed by some opposition elements in Nigeria, begins to sound reasonable.

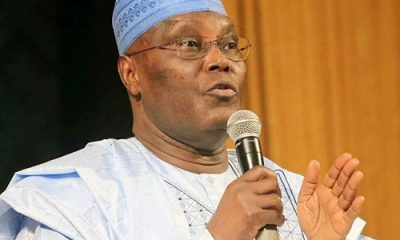

Peter Obi says, “Keep subsidies for a while. ” For Atiku Abubakar, it is “Guide the currency quietly from behind the curtain.” Rotimi Amaechi and Nasir El-Rufai want to “Push the tough structural work into another year.” On the surface, it feels safer. But history is clear on where that road leads.When Bulgaria began its transition from communism in 1990, its leaders were afraid of the shock that rapid liberalisation might cause. They freed some prices but kept politically sensitive subsidies in place, just as Peter Obi proposes.The subsidies drained the treasury, fuelled inflation, and collapsed the currency. They maintained a soft peg for the lev without reserves to defend it, exactly as Atiku Abubakar suggests for the naira. The peg broke, reserves vanished, and hyperinflation soared above 2,000 percent.They warned against “too much at once,” echoing Rotimi Amaechi and Nasir El-Rufai, and delayed the restructuring of state enterprises. Six years later, pensions were worthless, shops were empty, and the reforms they feared were forced on them in far harsher form.Nigeria today is on a very different trajectory. From his first day in office, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu took on the biggest distortions head-on. The petrol subsidy, which drained over four trillion naira a year, is gone.The naira now trades at a market-driven rate, closing the damaging gap between official and parallel exchange rates. The Central Bank has returned to orthodox monetary policy, raised interest rates to fight inflation, and cleared more than seven billion dollars in verified FX backlogs that had become a national credibility problem.That clearance restored credibility to our financial system and prompted the International Air Transport Association to remove Nigeria from its list of countries blocking airline funds. That reversal matters because it signals to every global balance sheet that Nigeria pays its obligations again.These decisions have delivered measurable wins in record time. The World Bank estimates subsidy savings of around two trillion naira in 2023 alone, with cumulative savings expected to exceed eleven trillion naira by 2025. This money is already being channelled into infrastructure, healthcare, and targeted social programmes across the country.Portfolio inflows in the last quarter of 2024 hit 5.6 billion dollars, more than the total of the previous two years combined and a clear sign that rule clarity is drawing money back to local assets. Non-oil tax revenue has grown by more than twenty percent year-on-year.Price pressure remains the public’s sharpest pain, but the first signs of relief are appearing. Official data show headline inflation eased in June 2025 from May, the first back‑to‑back moderation in many months. Disinflation never arrives in a straight line. What matters is direction and credibility of policy. Both are moving the right way.Yet this is the stage when voices, mostly driven by parochial interest, will call for a pause. Some will say households need breathing space and subsidies should return in another form. Others will argue that the naira is too weak and should be fixed at a stronger rate. There will be calls to slow fiscal clean-up until “conditions improve.” The bandwagon Association of Displaced Politicians, and the economists they front, want us to go back to Bulgaria 1990.Atiku Abubakar’s “acceptable rate” is the same illusion that emptied Bulgaria’s reserves and shattered its peg. Peter Obi’s “phased removal” is the same phased lie Bulgaria told itself until the economy collapsed. Nasir El-Rufai’s warning about “too much at once” is exactly what Bulgaria’s leaders said before the crash.Rauf Aregbesola’s “prioritise the people before the economy” mirrors Bulgaria’s fatal separation of the two, where the collapse of the economy destroyed the very livelihoods they claimed to protect – as if the economy is not the lifeline of the people. Rotimi Amaechi’s call to slow down is the same thinking that turned hardship into collapse.These are not alternative strategies. They are invitations to failure. They are the comfort-now, crisis-later prescriptions that have failed every country that tried them. And in every country where this happened, the politicians who sold them were gone by the time the bill arrived.The same politicians who had their turn in power and left Nigeria with a broken FX regime, ballooning subsidies, and a dangerous debt overhang now want to lecture about “protecting the people” by bringing back the very distortions that were killing growth. That is not protection. That is sabotage dressed as sympathy.A soft peg without deep reserves burns credibility while draining scarce foreign exchange. Partial liberalisation keeps the price distortions that breed shortages and arbitrage. Delaying the clean-up of state owned enterprises only compounds losses and pushes the real costs into the future.Once you retreat from hard reforms, investor trust evaporates, deficits swell again, and the cost of borrowing climbs. The longer you wait, the fewer options remain when the next shock comes. And when that bill finally arrives, it is always larger than it would have been if settled early.We have seen this film before. In 1990 Bulgaria called it gradual reform. By 1996, pensions were worthless, shops and shelves were empty, and the same politicians who promised a soft landing had fled the wreckage. The dire situation in.Bulgaria forced a desperate rescue the following year under conditions far harsher than anything they had wanted to avoid. I confidently repeat that, in Nigeria, those pushing this fantasy today will not be around to clean up the mess tomorrow. The only question is whether we have the discipline to finish the job or whether we hand the steering wheel back to the people who drove us into the ditch in the first place.Nigeria is not Bulgaria in 1990. We will not drift toward collapse because a few familiar names prefer popularity over responsibility. The alternative is to hold the line and let the compounding work in our favour. Clean our books and keep the auction rulebook predictable.Keep subsidy savings transparent and tied to visible projects so citizens can see where the money now goes. Keep monetary policy tight until inflation is back within a credible band and do not second‑guess the float with administrative fixes that markets will immediately punish.The IMF’s recent assessment underscored that Nigeria’s policy direction restores repayment capacity and anchors stability if pursued consistently. That is the quiet endorsement that disciplined reformers earn.Because this debate will not end here, it is worth meeting the counter‑arguments head on. Some say the pain on households is too high and too fast. The truth is the subsidy was never free. It was paid through bad roads, weak schools, failing hospitals and heavy borrowing that our children would service. Redirected savings are how you rebuild those services.Others say the float has made the naira too weak and that we should fix it at a stronger number. A number without reserves is only a promise. Markets test promises. Bulgaria failed that test in 1990 and paid for it in 1996. Nigeria should not repeat it.Another claim is that investors are not yet flooding in, so reforms are not working. They rarely flood in at the start. They watch for consistency, then move quickly. The late‑2024 surge in portfolio inflows is exactly that early signal. Hold the line and the longer term money follows.But as Mr President has always said and I am fully aware, Nigeria’s path is not without discomfort, but it is the only one that gives us a fighting chance to rebuild. The facts of upward, positive change are not in dispute.It is already producing the first signs of stability and renewed investor interest. The trajectory, if we hold it, leads to a competitive and credible naira, a fiscally stronger state investing in power, roads, and schools instead of fuelling petrol imports, and an economy where capital flows in because the rules are predictable and the numbers add up. Growth will no longer be hostage to oil prices alone, and the non-oil revenue gains of the current and past year are the proof.The opposition has shown that they have chosen collapse. Some former allies have joined them. The rest of us must hold the line. History has already written the ending for the road they want. We have chosen a different ending.There is no painless exit from decades of distortion. The choice is as stark as it is simple. Pain now with a recovery you can see, or comfort now with a collapse you cannot control. Bulgaria 1990 is the warning. Nigeria 2023 is the opportunity. We are already making in months the progress that took years for countries in similar positions. If we keep our nerve, stay transparent, and refuse the detours that have failed elsewhere, we will not just avoid Bulgaria’s trap. We will write the modern African recovery story others will study.And this is the truth we must hold to. The easy road has never led any nation to greatness. What we are doing under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu is hard, but it is necessary. We will be judged not by how loud the complaints were in the first year, but by the strength of our economy in the fifth and thereafter. If we see this through, the same Nigerians who today feel the sting will one day stand as proof that under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, Nigeria chose courage over comfort, and that choice changed the destiny of our nation for good and forever. And if we have the discipline to finish this path, it will be the one in which Nigeria wins.The Tiger’s Final Take: The Koko of the MatterBulgaria’s 1990 reforms teach us that gradualism in the face of structural crisis is not kindness. it is negligence in slow motion.Nigeria’s current path under President Tinubu is the opposite. It is tough, urgent, and forward-looking. If we hold this line, the discomfort will give way to resilience, competitiveness, and prosperity.Nigeria’s reforms today are closer to Bulgaria’s 1997 reset which is the one that finally worked, rather than to its failed 1990s drift. The difference is that Nigeria is doing it before hitting hyperinflation or a currency collapse.It is the hard road, but it is the right road, and it leads upward. This is the best time to Bet on Nigeria.A fellow of the Chartered Institute of Marketing (UK), O’tega ‘The Tiger’ Ogra is the Senior Special Assistant to President Bola Tinubu of Nigeria on Digital Communications, Engagement, and Strategy.